Chicken gets chilled. Consolidating and growing the Italian poultry sector

From the 1960s, new refrigeration technologies, marketing strategies, and organisational arrangements fostered the growth of the Italian poultry sector into one of Europe’s biggest.

Our journey through the history of industrial poultry farming and processing in Italy continues (and also ends) with the second large-scale poultry company established in the country: Arena. The company was founded in the late 1950s in Sommacampagna, near Verona. Whereas the first poultry company, Cipzoo, received substantial economic aid through the Marshall Plan, Arena had to stand on its own two feet from the start. Notwithstanding its less favourable beginning, Arena surpassed Cipzoo and became the most important Italian poultry company of the period.

In May 2023, the city of Sommacampagna hosted an exhibition on the history of Arena, “Pollo Arena. Una storia, tante storie” (Pollo Arena. One history, many histories). The video shows the exhibition’s inauguration. The organising committee also set up a website containing materials on the company history (in Italian): https://www.mostrapolloarena.org/

As discussed by Tessari and Godley (2014), there are three main reasons behind Arena’s success. The first is related to technological innovation. Existing meat chilling technologies employed ice and cold water. This resulted in so-called “wet chickens”, which Italian housewives were sceptical about. In the 1960s, Arena developed a pioneering method to chill broilers with cold air, instead of water, thus obtaining “dry chickens”, much more similar to the free range chickens which Italian families were used to. Arena’s chilling innovation became internationally renowned, and other poultry companies adopted it. A second reason behind Arena’s success had to do with its clever marketing strategies. Meat refrigeration was not only a problem during production, but also in retail. Most butchers and small-scale retailers did not have a proper refrigerator to store chicken meat, which requires a different temperature than beef or pork. Arena solved the issue by providing the retailers with branded refrigerator cabinets. Furthermore, the company put significant effort into its marketing strategies for consumers, which were meant to convince people that industrial broilers were as good and genuine as free-range chickens, e.g. by improving the products’ labelling and traceability. The third reason for Arena’s success is the company’s adoption of the best practices in chicken rearing and processing available at the time. An example is the implementation of vertical integration strategies, meaning that the company owned its supply chain. This allowed Arena to increase its control over the production process, and thus its efficiency. Eventually, also following the establishment of two more companies, AIA (1968) and Amadori (1969), Italy became one of the main players in the European poultry sector.

Labels from different Italian poultry companies. (Picture by author, exhibition “Pollo Arena. Una storia, tante storie”, Sommacampagna (VR), May 2023)

In the 1970s, the Italian poultry processing industry was thus quite advanced. Both production and consumption of chicken products were on the rise. Beside technological developments, other factors contributed to this growth. During the economic crisis of the mid-1970s, chicken meat became again central in State-sponsored food discourses, as already happened during the fascist period. Chicken meat was promoted as a cheap, healthy and nutritious alternative to red meat. As shown in the video below, the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry sponsored advertising to promote chicken consumption, ending with the slogan “a chicken on every table”, similar to the US New Deal’s slogan “a chicken in every pot”. This advertising was part of a larger State campaign to influence food consumption patterns and improve food education. A video reportage on the campaign reveals how it stemmed from the necessity of a more “rational” use of local products, evocative of 1930s discourse on autarky: “we need to situate food education within a larger planning politics, intended to rationally use all our agricultural and food resources”. This time, however, the goal of the State was not to encourage rural women to engage with “rational” poultry farming, but rather to persuade urban women to buy industrially produced chickens. Industrial production was emphasised as a guarantee of safe, hygienic and healthy products. However, it seems that Italian housewives still preferred the free-range chickens in the 1970s, considered a much better quality product when compared to the broiler (Tessari and Godley 2014, p. 1070).

Advertising on chicken meat, by the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry. Carosello, 1975. (Archivio nazionale del cinema d’impresa)

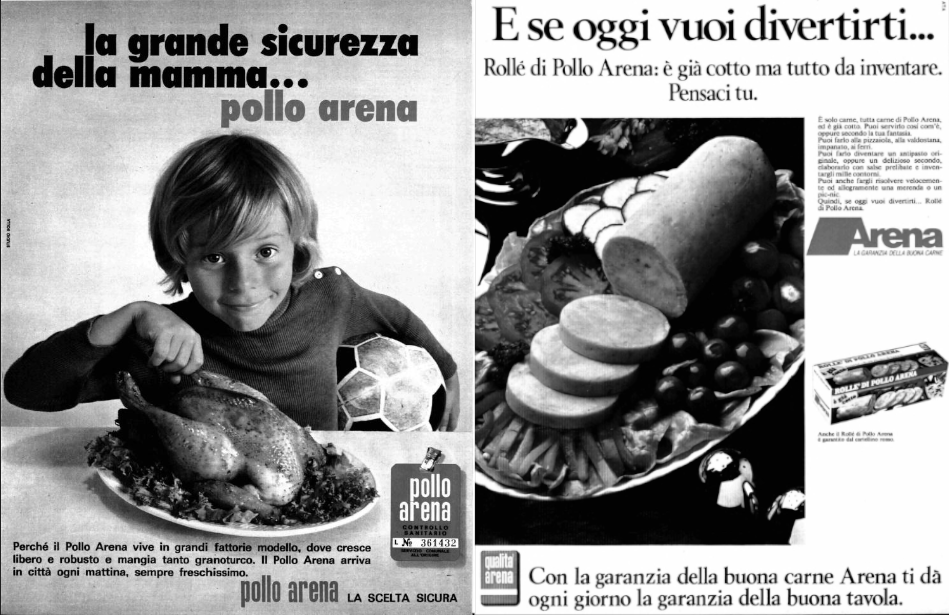

Poultry industry marketing efforts to innovate Italian food habits were based on conservative gender roles and family models, thus evoking at once modernity and tradition –not so differently from other food advertising of the period (Bottinelli 2014; Torresi 2011). For example, a 1970 advertising campaign by Arena (picture below, on the left) shows a happy child in front of a roasted Arena chicken, presented as “la grande sicurezza della mamma”, that can be translated as “Mom’s greatest certainty” or “Mom’s greatest security”, as the word “sicurezza” can be read with both meanings. Also in the case of highly processed poultry products, such as Arena’s chicken meatloaf (on the right), human labour is required. The product is especially recommended “if today you want to have some fun!”: although an oven-ready preparation, it allows for personalisation in its final serving -that would be the “fun”. In other words, the housewife will never be free from kitchen duties. Not even a pre-cooked product allows her to forget about dinner, as she is expected to “have some fun” by providing a personal touch.

Left: Radiocorriere, n.41, October 1970, p. 149 (via Internet Archive https://archive.org/details/Radiocorriere-1970-41/); Right: Radiocorriere, n. 38, September 1973, p. 93 (via Internet Archive https://archive.org/details/Radiocorriere-1973-38)

Our historical excursus on the relationship between technology, gender and chickens highlights how innovations in the poultry farming and poultry industry sectors had important implications for women, from the massaie rurali of the fascist period to post-WWII factory workers and consumers. A more detailed analysis would be necessary to assess whether techno-scientific innovation in the poultry sector improved the working conditions and possibilities of upward social mobility, especially for women. The visual representation of women, however, does not show remarkable improvements: from fascist regime videos to contemporary advertising, women were often represented as silent characters, who worked hard but joyfully –from the farm, to the factory, to the kitchen–, to make sure that tasty and nutritious chicken-based meals could be served on the Italian family table.

Ginevra Sanvitale

Bibliography

Bottinelli, S. (2014). Tradition and Modernity: Industrial Food, Women, and Visual Culture in 1950s and 1960s Italy. Food Studies, 5(1), 1.

Tessari, A., & Godley, A. (2014). Made in Italy. Made in Britain. Quality, brands and innovation in the European poultry market, 1950–80. Business history, 56(7), 1057-1083.

Torresi, I. (2011). The (Gendered) Construction of ‘Home’ in Contemporary Italian and US Food Advertising: Or, What Is Home Without a Mother?. In Minding the Gap: Studies in Linguistic and Cultural Exchange (pp. 235-243). Bononia University Press.