Chicken goes to war. The symbolic and material significance of poultry in times of conflict

During WWII, poultry became central for both fascists and anti-fascists, providing nutrition to sustain fighters and civilians as well as metaphors to discuss the socio-political context.

In the 1960s, singer and songwriter Chicho Sanchez Ferlosio wrote one of the most famous songs about the Spanish Civil War (1936-39). The song, titled Gallo rojo, gallo negro (“Red rooster, black rooster”), talks about the struggle between the fascist nationalists (symbolised by the “black rooster”) and the republicans (the “red rooster”). “The black rooster was big, but the red rooster was brave,” proclaims the song, showing the symbolic importance of animals like chickens, hens and roosters, which here and elsewhere are used as metaphors for human behaviour. However, historically, chickens did not only have a symbolic significance in human conflicts.

Moving from Spain to Italy, poultry became a much sponsored food under the fascist regime, and in WWII. Poultry production was a crucial component of the autarky policy enforced by the regime. A primary target for Mussolini’s autarky campaign were women, and particularly rural women. In 1933, the fascist party established the organisation “Massaie rurali” (Rural farm-women) as a set of “Fasci Femminili” (female groups), the women’s league of the party, targeted towards rural women. This organisation points at the relationship between gender, poultry and technology, as rearing chickens was a crucial task for the massaie rurali. The organisation sponsored a vast program to increase women’s commitment to domestic poultry rearing. Training courses were held, as well as contests, with the intent of increasing women’s skills and stimulating their commitment to the task. Techno-scientific advancements were a crucial component of these training sessions.

“Rabbit and poultry farm launched in Varazze, under the initiative of the Massaie Rurali group” Giornale Luce, May 6th, 1936.

The video above shows an initiative by the Massaie Rurali group of Varazze (near Savona), which built a local breeding farm for rabbits and poultry. The Massaie are briefly acknowledged at the beginning of the video, but the discourse is focused on the “rationality” of the breeding farm, and on promoting the autarky policy, as well as the superiority of Italian breeds. As the commentator of the video claims, “In the model chicken farm, beside local breeds, there are also some American hens. However, they are not comparable to local ones, because their eggs are much smaller. As you can see, also in this case you have everything to gain in giving priority to national products”.

The fascist plans for autarky became even more complex, as well as compelling, with the start of WWII, as fields became war zones and farmers became soldiers. As shown in the video below, poultry rearing was not anymore just a rural activity, because the fascist party encouraged the organisation of “wartime chicken coops” in urban settings, meant to sustain the country and further affirm the autarky policy. Women remained essential to this task, and also urban women were called to engage in poultry rearing for the sake of the nation. Luckily, this and the other fascist efforts were ultimately unsuccessful in securing the Axis’ victory in WWII.

“Wartime agriculture: picking potatoes in the garden of the University. Wartime chicken coops organised everywhere” Giornale Luce, August 11th, 1941

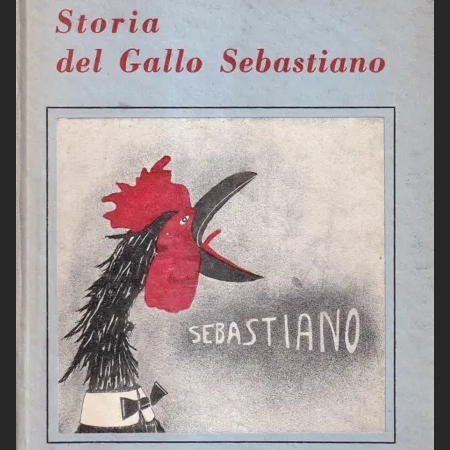

But chickens also had a role in the anti-fascist resistance, symbolically and materially. In 1940, teacher and anti-fascist militant Ada Gobetti published the children’s book “Storia del gallo Sebastiano ovverosia il tredicesimo uovo” (The story of Sebastiano the rooster, that is, the 13th egg). Sebastiano can be undoubtedly considered a “red rooster”, in the sense of an anti-fascist rooster. In Ada Gobetti’s words, “The strange little rooster, who never succeeded in walking in step with the others, who always did exactly the opposite of what was expected of him, on the contrary embodied in himself a symbol of the need for anti-conformity that has been alive in all children since the beginning of time. It assumed a particular meaning and value in that period of almost absolute and complete conformity, because Sebastiano the rooster was born at the height of fascism.” (quoted in Alano, 2012:70) The book contained several implicit references to fascism, but was able to escape censorship and many children read it.

On a more pragmatic level, poultry products also contributed to the success of the anti-fascist resistance by providing nutrients to the partisan fighters. As suggested by Carrara and Salvini, the same autarkic principles which supported the fascist regime might have also contributed to its demise, as partisan fighters, like most Italians, were used to frugality. Amidst the several difficulties and deprivations faced by the WWII anti-fascist resistance, poultry products (whether eggs or meat) were a very important source of protein, as they were more readily available than other animals.

Ginevra Sanvitale

Bibliography

Alano, J. (2012). Anti-fascism for children: Ada Gobetti’s story of Sebastiano the rooster. Modern Italy, 17(1), 69-83.

Belmonte, F. (2013). Gallo rojo, gallo negro, chanter la dissidence. De la rue à l’histoire. Lengas. Revue de sociolinguistique, (74).

Carrara, L., & Salvini, E. (2015). Partigiani a tavola: storie di cibo resistente e ricette di libertà. Fausto Lupetti.

Garvin, D. (2022). Feeding Fascism: The Politics of Women’s Food Work. University of Toronto Press.

Willson, P. (2003). Peasant Women and Politics in Fascist Italy: The Massaie Rurali. Routledge.